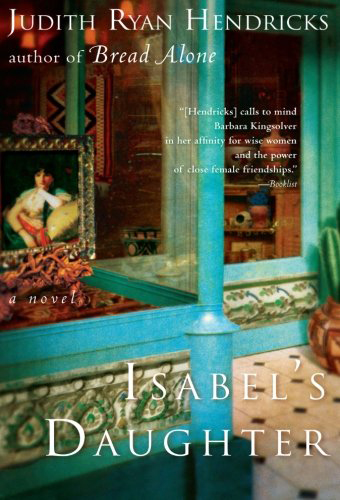

Isabel’s Daughter

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, Books-A-Million, Bookshop, Collected Works Bookstore, IndieBound, Powell's

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, Books-A-Million, Bookshop, Collected Works Bookstore, IndieBound, Powell'sPublished by: Harper Perennial

Release Date: June 29, 2004

Pages: 400

ISBN13: 978-0060503475

Overview

After a childhood spent in an institution and a series of foster homes, Avery James has trained herself not to yearn for the mother who gave her up. But her safe, predictable life changes one night at a party in the home of a wealthy Santa Fe art dealer, when she stumbles upon the portrait of a woman who is the mirror image of herself.

Avery has found her mother, Isabel Colinas, an artist who died eight years earlier in a tragic accident. Slowly but inevitably, she is compelled to discover all she can about the woman.

Searching for Isabel—in her work, in the stories of friends, rivals and lovers, and what’s left of Querencia, the old miner’s cabin that was her haven—Avery is drawn into complex relationships with the people who knew her mother, and into an unexpected love.

As she weaves together the threads of her mother’s artistic heritage, her grandmother’s skills as a curandera or healer, and her own talent for cooking, Avery learns that, while discovering Isabel provides a certain resolution in her life, it’s discovering herself that brings lasting happiness.

Discussion Guide

Download the discussion guide here

Praise

(click to enlarge)

Friday the 13th turned out to be a lucky day for me…Isabel’s Daughter makes the NYT Crossword Puzzle.

“Engaging…a page-turning puzzle.”

—USA TODAY

“(Hendricks) calls to mind BARBARA KINGSOLVER in her affinity for wise women and the power of close female relationships…readers of this fine novel won’t want to tune out any part of Avery’s life.”

—Booklist

“A great read with a plot that keeps the pages turning…”

—The Santa Fe New Mexican

“Warm-hearted and realistic with a touch of humor…this wonderful read offers an escape the reader will be reluctant to return from.”

—Daily Oklahoman

“Avery James is a great creation—contrary, confused, but never less than convincing.”

—Image Magazine

"Isabel's Daughter" is a journey of discovery, a novel that is heartening and not heavy, a thoughtful summer read.”

—The Denver Post

“Hendricks gets the details right in this graceful, optimistic novel…an engaging, well-written look at the tension between independence and relationship.”

—Albuquerque Journal

Backstory

My first glimpse of New Mexico was through a car window as I traveled with my family on the first of many summer expeditions from St. Louis to California along Route 66. I was nine years old, and I was most interested in spotting more out-of-state license plates than my brother and bugging my father to stop at souvenir stands.

But something about the place stayed with me long after those vacation trips had become fragmented bits of family nostalgia. Maybe it was the Indians selling baskets and jewelry in Gallup restaurants. Maybe it was the music of spoken Spanish, or the dusty pueblos or the way the stars filled up the black night sky from rim to rim.

Years later when I was dating my husband Geoff, I visited him in Santa Fe, where he was working. On the ride from the Albuquerque airport to Santa Fe, I sat mesmerized as the landscape slid past—rolling hills covered with pinon and juniper, red sandstone bluffs against piercing blue sky—both exotic and familiar at the same time, and I began to feel a kind of thrum, like low voltage electricity dancing over my skin.

By the time I got around to writing my second novel, the idea of New Mexico had been percolating on the back burner for quite a while—not even really an idea, but something more nebulous. A mood. A sense of possibilities.

In the fall of 2001 I spent two months in Santa Fe, researching Isabel’s Daughter, and immersing myself in the magic of the Southwest. I read a lot of books about the area, both fiction and nonfiction, and it seemed to me that the logical story to set in New Mexico would be a ghost story or a mystery. I think Isabel’s Daughter is both of those things, but not in the usual sense. The story’s ghosts are in the hearts of the living. Instead of a “Whodunit,” the mystery is more a “Who am I?

It’s a story about discovering your past and your future, learning who to love and who to trust. It about how we all—no matter what our circumstances—discover who we are and take our place in the world.

Excerpt

I read where some famous doctor said that babies are like little blank slates, waiting to be written on, waiting to be made into whoever they will be.

This, as any baby knows, is a load of horseshit. Babies are born with the seeds of who they’ll be already inside them. When you plant a sunflower seed, you get a sunflower. If it gets too much water or not enough light or the soil’s too heavy, it might grow scrawny or droopy. The leaves might shrivel and drop. It might die. But it’s not going to come up a columbine.

Babies can see and hear and smell and feel. They know all kinds of stuff they’re not supposed to know. But they can’t tell anyone. And by the time they learn how to talk, they’ve forgotten what they knew.

So it was no big surprise to me the first time I heard the story of how I was found. After all, I was there. And long after I’d forgotten why, I had dreams about a darkness, an emptiness that seemed to well up from beneath my feet and swallow me.

Alamitos, Colorado—in English, the name means “little cottonwood trees.” It’s a small farm town in the San Luis Valley, down by the New Mexico border. High and dry, flat and windy, ringed by mountains—Sangre de Cristos to the east and south, San Juan, La Garita and Conejos-Brazos to the north and west. White frosted in winter, dirt brown in spring, green in summer. The cottonwoods that it’s named for turn gold in autumn, and the air is thick with the damp earth smell of potatoes, piled at the edges of fields, stacked in bins and boxes, truckloads and railroad cars full.

Besides potatoes, the valley’s other big claim to fame is the Great Sand Dunes—fifty square miles of sand, dropped when the prevailing westerly winds run into the Sangre de Cristos. I lived in Alamitos for the first thirteen years of my life and only saw the dunes once. I knew without being told that they were a freak of nature, didn’t belong there—a pale and shifting ocean, high in the Rockies.

San Juan Avenue runs straight through the middle of town. There’s the square brick post office and the El Azteca movie theater with its pink and green neon sign, a couple of banks, Corie’s Café on one side, Tina’s Cantina across the street. There’s a hardware store and Raymond’s Corner Market, where we used to go in the afternoons to drink lemon slushees and watch the older kids from the public high school smoke and make out.

Railroad tracks cut across San Juan Avenue, dividing the town neatly in half. On the north side, that’s where the poorest people lived, behind crumbling adobe walls, or in wood frame houses with peeling paint and tarpaper roofs. Rusting cars bloomed among the weeds, and skinny mongrel dogs laid on porches.

On the south end of town, the streets were wide, the trees were tall and the houses were historically significant, although not always kept up nicely. On Selden Street was the biggest house of all, a Victorian pile of red brick called the Randall Carson Foundling Home.

That’s where I made my official debut in the basement one frigid January night, wearing a soiled diaper, an undershirt embroidered with flowers; and wrapped in a bath towel from the Stardust Motor Inn.

The story goes that the janitor, a nearsighted Arapaho named Charlie Elvin, was in a hurry to lock up and go home to his nice warm trailer where his wife and his dinner waited. Without his glasses, he thought the bundle he bumped with his work boot might be some stray dog that had crawled into the relative warmth of the furnace room to die.

Charlie might have been half blind, but his ears were sharp. He heard a jerky, gasping sound. The bundle was breathing. Crouching down, he found himself looking into a pair of small, dark eyes. Eyes, he later told his wife, that were somehow not right, although at the time, he couldn’t say why.

He picked up the baby, and just as quickly set it down. It smelled like his chicken coop on a summer afternoon. He ran to the door. Then back to check the baby.

“I’ll be right back,” he blurted, sprinting for the night duty station.

Annette Colby, the nurse on duty that evening, was a plump, sensible young woman with short brown hair. When Charlie burst into her tiny office, babbling about a child in the basement, her first thought was that one of the children had fallen down the steep stairs. She lunged for her black bag.

“I’ve told the board a thousand times to put a gate in front of those stairs—”

“No ma’am.” Charlie shifted his weight impatiently. “It’s a baby. Poor little thing looks half froze.”

She narrowed her pale blue eyes at him. Charlie’d been known to take a nip, but he’d been going to AA for nearly five years now. “That’s not possible,” she said calmly. “How would a baby get in the furnace room?”

“Damned if—‘scuse me. I don’t know, lady, but it’s there. I’m tellin’ you. Come on with me.”

Her own panting filled her ears as she followed Charlie down the stairs and through the long, dim hall that smelled of floor wax, taking two steps to his one. Through the high windows she could see huge, silent snowflakes drifting between naked tree branches. The wind had stopped momentarily.

“I don’t hear anything,” she said as he pushed the door aside for her. “Is it…?”

“Was when I left.”

“Did you bother to—” The baby interrupted her with an impatient wail. “Dear Heavenly Father.” She bent and picked up the shivering bundle, tucked it inside her jacket, towel and all, wrinkling her nose at the stench. “Charlie. Run upstairs and call Dr. Tatum. Hurry now.”

As she climbed the stairs, lost in her conversation with God, she felt a tug at her blouse. She looked down.

Locked in a tiny, filthy fist was the necklace Annette’s mother had given her—a gleaming butterfly—made by a silversmith named James Avery. Annette took it as a sign from God, and she named me James Avery. When in the course of the doctor’s examination, they discovered I was a girl, Annette simply inserted a comma.

Name: James, Avery.